Alexandre Moutouzkine

Alexandre Moutouzkine

Alexandre Moutouzkine will perform at the Miami Music Festival and the Beijing International Music Festival and Academy. For more information plase click the respective photo below.

Alexandre Moutouzkine

Alexandre Moutouzkine

Hidden Melody

Friday, December 2nd, 8:00 p.m.

"Young Promise" competition winner and piano/composition master’s degree candidate at the Manhattan School of Music, Alexandre Moutouzkine premieres a new orchestral work with the New York International Symphony Orchestra. The concert highlights the premiere and three solo concertos.

Chamber Music International excels on Schumann, stumbles with Mozart and Brahms

Richardson — I have seldom heard a concert that left me with more mixed feelings than Saturday’s Chamber Music International concert at Richardson’s St. Barnabas Presbyterian Church.

First, the good: Alexandre Moutouzkine’s playing is intellectual without being cold, precise without being fussy, interesting without being odd. Moutouzkine has performed with Chamber Music International before, and is always a welcome guest here in Dallas.

This time, his performance of Schumann’s Carnaval was all these good things and more. This utterly transfixing piece has 20 numbered sections, plus two that are unnumbered. Each section also has a name: from Schumann’s own alter egos Eusebius and Florestan to Chopin and Paganini to Chiarina (Clara Wieck, Schumann’s student and future wife) and Estrella (his then-fiancée, Ernestine von Fricken). This assortment of seemingly unrelated parts is united by repetition of the notes A, E-flat, C, and B, which in German notation are A-S-C-H: a musical cryptogram with several significant meanings for Schumann. Moutouzkine explained all of this critical information in charming remarks preceding his performance, enhancing the listeners’ experience.

The remainder of the program was more problematic. The first piece on the program, Mozart’s Duo in B-flat for Violin and Viola, K. 424, was performed by violinist Paul Rosenthal and violist Atar Arad. While Arad, also a CMI regular, has a gorgeous viola sound, and the piece itself is terrific, Saturday’s performance was beset by pitch problems and some sliding shifts from Rosenthal that were not in keeping with Classical style.

Unfortunately, problems continued into the Brahms Quintet for Piano and Strings in F Minor, Op. 34, the final piece on Saturday’s program. Here, Moutouzkine, Arad, and Rosenthal were joined by CMI Artistic Director Philip Lewis on violin and Jungshin Lim Lewis on cello. It was delightful to hear the Lewises perform on one of the programs they work so hard to put together, and the Brahms is a marvelous piece. Still, pitch continued to be a problem, and balance was often piano-heavy.

The Schumann alone, though, made this a performance well worth attending

Pianist Moutouzkine stellar at Symphonia

Sunday afternoon’s concert by The Symphonia Boca Raton had a loose and handmade feel to it, with decent performances by the group of some unusual repertoire, and a standout appearance by a guest soloist.

Alexandre Moutouzkine, a Russian-born pianist, was the soloist for two works, the rarely heard Ballade (in F-sharp, Op. 19) of Gabriel Fauré, and the Aubade of Francis Poulenc. Moutouzkine is a wonderfully fluid pianist, with tremendous finger independence that stood him in good stead for the Fauré’s complex inner voices and the Poulenc’s hyper-Jazz Age effusions.

Leading the Symphonia, which has no permanent conductor, was another guest, the Hartford Symphony’s Carolyn Kuan. She led the Symphonia with authority and an expressive left hand that she used for most of the colors she wanted to bring out.

The Fauré Ballade, which Liszt famously dismissed as too difficult, is heavily indebted to Chopin but has more elusive harmonies, as does much of Fauré’s infinitely subtle piano music. Like Chopin’s concerti, this 20-minute work is also modestly orchestrated, with the instrumentalists in a supporting role.

Moutouzkine showed total command of the keyboard from the beginning, with a pure, singing tone in the nocturne-style opening section, and remarkably strong and clean contrapuntal lines in the second segment. In addition to tossing off the passages of filigree with ease, he gave this gentle music shape and an emotional arc; you could feel the drive of the faster sections and luxuriate in the serene landscape he constructed in the slower, poetic passages.

You need that in pieces as modest as the Ballade, but it’s even more important in a choppy work like the Aubade, which after all was designed to be ballet music. The first extended piano portion of this unusual piece, the Toccata, was played with frenetic, almost cartoonish speed, and the A major rondo (Diane et ses compagnes) moved along briskly, but with careful attention to the gracefulness of the tune.

The same care and sparkling virtuosity were in evidence through the rest of this wildly eclectic piece. It could probably have used some more rehearsal to make it hang together a little better and clear up some of the roughness in the Symphonia, though overall this was a charming and enjoyable performance.

Moutouzkine played an encore, one of the many jazz etudes by the Russian composer and jazz pianist Nicolai Kapustin. He is a hugely popular composer for the audience that likes jazz crossover like Claude Bolling or Jacques Loussier, though Kapustin is far more aggressive. Moutouzkine played with brilliance and astonishing control in this blizzard of bebop, making a good case for a piece that doesn’t really deserve it. But he is a splendid pianist; his one drawback is that he might be too facile a finger acrobat, and he will need to make sure he puts that to good use and resists the temptation to just dazzle.

Carolyn Kuan. (Photo by Aaron Locke)

The concert opened with early Copland, his Music for the Theatre. It’s a canny reflection of the music of the 1920s as filtered through a man with French modernist study under his belt, and in addition it has hints of the populist style that would make him not just a respected American composer but a beloved one.

Here again, things could have been a little tighter, but there was good solo playing from the woodwinds, particularly Jeff Apana’s English horn solo in the Interlude, which he played with a warm, fat sound that filled the Roberts Theater. (Kuan did a nice onstage interview with him about his instrument during a set change to bring on the piano for the Fauré.) The performance had the right spirit, in any case, cheeky and lively.

The concert closed with the Symphony No. 38 (in D, K. 504) by Mozart, known as the Prague Symphony. Kuan led this well, with good attention to its muscle in the first movement and a generous, wide-open feel for the slinkiness of the second movement. The finale got off to a very brisk start, but the Symphonia was not able to maintain it to the end, and things were slower by the final bars.

But there was much to like about this performance, mostly its crispness in the service of the Mozartean idiom, in which a chamber orchestra gets closer to the actual size of groups the composer would have known. You can hear the forcefulness of Mozart’s writing more clearly in these smaller groups, and the Symphonia gave the work a strong, engaging read.

Alexandre Moutzoukine reveals new worlds in Rachmaninoff, Schumann

Constructing a recital of just two pieces might seem to limit the number of chances to take in the whole personality of the performer. But Rachmaninoff's Thirteen Preludes and Schumann's Carnaval are two exceptionally sprawling and varied canvases, and on Wednesday night, Alexandre Moutouzkine proved a pianist exceptionally sensitive to worlds the composers might have hoped for beyond the written page.

In his Philadelphia Chamber Music Society recital debut at the American Philosophical Society, Moutouzkine revealed a series of beautifully detailed character sketches - one by an artist (Rachmaninoff) who was a progressive posing as a traditionalist, and the other (Schumann) whose progressiveness still boggles.

The Schumann was the greater accomplishment - a sharper, richer vision. Moutouzkine had a lovely range of sounds in the Rachmaninoff, and a keen ability to bring out the best qualities in a piece that connects with the composer's piano concertos and four-hand repertoire. His technique was crystal-clean. In the fifth prelude (G major), Moutouzkine seemed consciously to evoke a harp, a watery repose swiftly revoked by the Liszt-like bark of the sixth (F minor).

But Schumann's Carnaval was in a different category of sophistication. The material, of course, has incredible dramatic range (perhaps even a recurrent mood disorder). Moutouzkine understood Schumann's erratic emotional line as its genius, underlining rhythmic and tempo distortions to mercurial ends - ecstatic, then flaccid, and back. The 21 movements make for a parade of characters real and imagined, domestic and fictitious - a harlequin, Chopin, Schumann's love objects. Moutouzkine drenched the atmosphere in distortion and layers: frustration when something is constantly getting in the way; the impetuousness of three ridiculous notes that keep interrupting the show; how a dance as reliable as a waltz can grow slippery; childlike curiosity; flashes of anger and ecstasy; and the incredible charm of a well-paced deceptive cadence. All these Moutouzkine presented as friends to be prized for their eccentricity.

Only Bach could have restored order, and he did, in an encore, but one buoyed by unusual amity. Rachmaninoff's transcription of the "Gavotte" from the violin Partita No. 3 was crisp to the point of being carefree. He might have done without the second encore, Ernesto Lecuona's Mazurka Glissando (though it was played with incredible polish), but the piece did tell the audience it was time to quiet their praise and go home, and they complied.

The Classical Music Guide Forums

IKIF16th International Keyboard Institute and Festival at Mannes College

July 23rd, 2014

Beethoven: Sonata No. 13 in E-Flat Major, Op. 27, No. 1

Rachmaninoff: Morceaux de Salon, Op. 10

M. C. Graves: Currency

Chopin: Twelve Etudes, Op. 25

Before this concert started IKIF Founder and Director Jerome Rose came to the stage to give his usual reminder to turn off cellphones and electronics, then added some news the audience was clearly happy to hear: That despite reports to the contrary, it is the intention of the management to hold the Festival again next summer, though the location has not yet been determined. (Mannes College will be moving next year, and apparently will not be able to provide space for the IKIF in the summer of 2015.)

The young Russian-American pianist Alexandre Moutouzkine makes one aware of how inadequate stereotypical expressions are when describing some of the remarkable young musicians before us today. As we have learned not to make assumptions about pianists necessarily having a proclivity for the music of composers of their own ethnicity, so, too, we see more and more that describing pianists such as Mr. Moutouzkine as “serious musicians” versus “virtuosos” makes no sense. Mr. Moutouzkine is a sensitive, thoughtful pianist who never plays a note outside of a musical context. And one hell of a virtuoso, too!

The opening of the Beethoven Sonata had a lovely, natural flow, and the dynamic contrasts in the second movement were well displayed. Most impressive, for me, was that I heard the second and fourth movements with a clarity I hadn’t heard before because of the pianist’s astute gauging of fast, but not excessively fast tempi, minimal pedaling and, of course, those wonderful fingers of his.

The Morceaux de Salon are not Rachmaninoff’s best pieces. Only one or two of them were familiar to me. But I enjoyed these performances, which were given with a consummate understanding of the composer’s idiom. The ruminative Nocturne, the Barcarolle, which had a shimmering accompaniment to a theme which seemed to express longing, the nostalgic Melodie and the smoldering Romance contrasted with the frothy Waltz, the controlled wildness of the Humoresque and the high spirited Mazurka.

The pianist addressed the audience before playing Currency, by his friend, Michael Christopher Graves, who was present, but said he would not reveal exactly what the piece represented. This mystery will be revealed, it seems, when he plays it again at his upcoming recital at Merkin Hall. If I heard clearly, it seems to be based on a motif of four notes, all within the distance of a major third, which is then turned around, played against itself in another voice, and later develops further with very brilliant passagework. Mr. Moutouzkine performed this enormously complicated work from memory, and played with remarkable clarity while pummeling the instrument.

Chopin expanded the technical horizons of the piano as well as the repertoire with his etudes. But an audience is not interested to hear the struggle of the obstacles the performer faces. It wants to hear the obstacles overcome with grace, ideas, imagination and artistry. Which Mr. Moutouzkine did. With apparent ease.

Among the highlights:

The sotto voce playing of the fourth (A Minor) etude, with several original touches.

The more serious approach to the fifth (E Minor) Etude than the “happy frog jumping about” Rubinstein interpretation (though I liked that, too), and with a particularly gorgeous playing of the melody in the middle section.

The ease with which Mr. Moutouzkine played the thirds etude, allowing him to do lovely things with the accompaniment despite the great speed.

The speed with which he played the 10th Etude (faster than Lhevinne), his bringing out (as he also did in other etudes) of interesting middle voices, and the increasing intensity with which he approached the end of the series. One item which might have been a bit more effectively gauged was that he was already playing so loudly in the last etude it was impossible to get any louder in the final C Major section.

If I had to pick one etude which impressed me the most it would probably be not one of those already mentioned, but the seventh, in C-Sharp Minor. Mr. Moutouzkine wrung all possible expressivity out of it with a huge range of dynamics and sometimes extreme, but always effective rubato. A high point of the concert, indeed.

The recital concluded with Lecuona’s delightful and exuberant Mazurka Glissando.

This is an pianist I’d like to hear again!

Donald Isler

Review: Pianist's fine support sets Astral trio's tone

By Peter Dobrin, Inquirer Music Critic

POSTED: November 18, 2015

Exhibit One in the case for Astral Artists as a wise talent-spotter is Alexandre Moutouzkine, the Russian-born pianist who has spent the last half-dozen years impressing local listeners in a variety of chamber music, solo-recital, and concerto appearances. His latest coup was Sunday at the Trinity Center for Urban Life, where he joined two other superb Astral "graduates" in piano-trio repertoire that stretched the genre a bit.

In January, Moutouzkine will step into the Philadelphia Chamber Music Society's solo spot (with Rachmaninoff's Thirteen Preludes and Schumann's Carnaval), but on Sunday his role was that of colleague, and an attentive colleague he was. He constantly looked over to violinist Ayano Ninomiya and cellist Clancy Newman to anticipate an entrance or time a passage in Beethoven's Piano Trio in G Major, which no doubt contributed to the feeling, in the galloping last movement in particular, that this was a puzzle whose pieces were tapped into place with a great deal of thought and preparation.

But Moutouzkine wasn't merely attentive. He was beneficence playing out in real time - and having influence. After the pianist's upward-moving rush of notes popped up in the noble second movement like so many pizzicato notes, their shape and weight were echoed later in a downward gesture by the violin. In a low doubling with cello, Moutouzkine nestled firmly within the bloom of that sound.

One of Moutouzkine's most compelling qualities is a rhythmic crispness that stems from landing on the forward edge of the beat (while never rushing). This quality contributed enormously to the verve in Smetana's Piano Trio in G Minor, which spills over with emotion; all three players captured its crevices of drama and, in places, surprising ambiguities.

The program's second half was overtaken by more populist spirits: a movement from Lera Auerbach's Triptych - The Mirror With Three Faces. The movement - with a name that takes longer to say than the music takes to hear: "Folding - Postlude (Right Exterior Panel)" - might have left you feeling that a haze of friendly ectoplasm had floated into the room. It didn't seem like important repertoire, and neither did the Café Music by Paul Schoenfield. But both were good-humored works by living composers that at least gave the piano trio a contemporary reference in the minds of listeners.

pdobrin@phillynews.com

215-854-5611

PIANO INSTITUTE

Session 1: June 6th - June 25th (Solo Piano)

Session 2: July 6th - July 24th (Collaborative Program/Solo Piano)

PIANO PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS

- Weekly private lessons and masterclasses with acclaimed faculty

- One open lesson with each guest master teacher Yoheved Kaplinsky and Anton Nel

- Weekly recital opportunities

- Chamber music study in collaboration with the MMF Orchestra Institute

- MMF Piano Concerto Competition in which the winner performs alongside the MMF Symphony Orchestra at the New World Center concert

- Classes and forums in technique, artistry, musicianship and career management

- Instrumental and Vocal Collaborative training for pianists interested in gaining additional experience

Solo Piano Institute

The MMF Piano Institute is a rigorous and in-depth program for devoted and exceptionally talented young pianists, ranging from the pre-college to conservatory level. The goal of the program is to offer solo and collaborative pianists a stimulating environment in which to study and explore various musical philosophies. With an open-class policy, students have the unique opportunity to observe, participate and learn from the insights of each faculty artist and student. Additionally, scheduled open forums examine structural analysis, the dynamics of performance, thematic scope, and career management. In the tradition of Schnabel, Rachmaninoff, Neuhaus and Liszt, the MMF Piano Institute encourages the philosophy that a diversity of ideas inspires and facilitates artistic freedom.Under the guidance of acclaimed faculty Alexandre Moutouzkine and Ching-Yun Hu, participants receive weekly private piano lessons, intensive technical and artistic seminars, career forums and master classes. Performance opportunities include solo recital and chamber music study in collaboration with the MMF Orchestra Institute, coached by piano and instrumental faculty.

Alexandre Moutouzkine

Encore!

Sunday, November 15, 2015 3:00pm

Trinity Center for Urban Life

2212 Spruce Street, Philadelphia

Laureates return to the Astral stage, in both contemporary

and beloved, time-honored piano trios.

Ayano Ninomiya, violin

Clancy Newman, cello

Alexandre Moutouzkine, piano

Beethoven Piano Trio in G Major, Op. 1, No. 2

Smetana Piano Trio in G minor, Op. 15

Lera Auerbach selection from Triptych—The Mirror with Three Faces

Paul Schoenfield Café Music

Alexandre Moutouzkine

Moutouzkine at PYPA: Many pianists in one, all intriguing

A paradox, perhaps, but it's a significant marker of individualism that every time Alexandre Moutouzkine appears, he sounds like a slightly different pianist. The basic character of his playing morphed even in a single recital, Thursday night, part of the Philadelphia Young Pianists' Academy (PYPA).

Many listeners came to know Moutouzkine through his affiliation with Astral Artists, for which he devised in 2011 an unusually inventive live transcription of Stravinsky's The Firebird as the sound track to the animated short Who Stole the Mona Lisa?

He brought an orchestrator's fine ear Thursday night to Rachmaninoff's Études-Tableaux, Op. 39. In the "No. 2 in A Minor," which shares something with the composer's The Isle of the Dead even beyond the appearance of the dies irae, Moutouzkine shone a variety of lights behind certain phrases and notes, simultaneously with an unusual degree of differentiation. In the "No. 6 in A Minor," he invoked Liszt in the growling, repeated opening figure. Much of this music is overwrought, and Moutouzkine, though passionate, is not prone to brutality or exaggeration. Clarity and brilliance propelled the last etude, "No. 9 in D Major," gathering intensity to a rather thrillingly paced last few bars.

That Moutouzkine was able to do what he did on the instrument at his disposal was a trick in itself. Rather than the usual Steinway the Curtis Institute keeps on the stage of Field Concert Hall, PYPA brought in a Yamaha that was limited in its colors and generally of a less-than-pleasant sound.

Better served by the instrument were the less varied demands of Mozart's Sonata in B Flat Major, K. 281. Moutouzkine found a spirited view of the piece through elegant ornamentation and attention to specific kinds of articulation. Dallapiccola's Sonatina Canonica in E Flat Major on Caprices of Niccolo Paganini was a welcome oddity, with its opening music-box movement a mix of charming and spooky, and an occasional Stravinskylike turn of phrase.

If assembling the order of pieces has much to do with emotional impact, Moutouzkine's opener was a master stroke. Rachmaninoff's transcription - a rewriting, really - of Bach's Partita in E Major for Violin is an essay on three types of grandness, and here Moutouzkine's blend of clarity and excited passion were especially flattering to the music. The opening brilliance, and stately, undeniably pianistic contrapuntal layering of the second and third movements made complexity not only a virtue, but also a platform for great joy. Bach is hard to improve on, but here the source, revisionist, and interpreter reinforced one another's strengths across the centuries.

Alexandre Moutouzkine

Moutouzkine, una revelación pianísticaTeatro Colón

Jueves 23 de Julio de 2015

Escribe: Andrés Hine

Programa:

A. Scriabin: Concierto para piano en Fa sostenido Menor, Op. 20

A. Bruckner: Sinfonía No. 6 en La Mayor

Orquesta Filarmónica de Buenos Aires

Director: Arturo Diemecke

Solista: Alexandre Moutouzkine

Bajo la batuta de Arturo Diemecke se inicio la velada con el Concierto para piano de Scriabin. Obra de su juventud, fue escrita en unos pocos dias en el otono de 1896, aunque no terminó completamente la orquestación hasta Mayo de 1897. El compositor se encontraba todavía en su periódo romántico y la obra tiene pasajes que podrián haber venido dirctamente de la pluma de Chopin. Los tres movimientos, Allegro, Andante y Allegro Moderato, cada uno con sus caractrísticas individuales, forman una unidad delicada y atrayente. Alexandre Moutouzkine se desempenó como solista en este concierto, el único que escribó Scriabin para piano, y cumplió un destacado trabajo que puede ser analizado desde dos puntos de vista. Por un lado de un sonido abundante donde lució su técnica perfecta. Por otro lado sedujo con la calidez de su expresión, la belleza y redondez de su sonido, y la inteligencia constante que muestra en el fraseo y en la exposicion estructural de la obra. Un gran artista para tener permanentemente en cuenta.

Bruckner compuso su sexta sinfonía an La mayor entre Septiembre de 1879 y Septiembre de 1881. Consta de cuatro movimientos Maestoso, Adagio, Scherzo y Finale (movido pero no demasiado) y aunque posee muchas de la características de sus otras sinfonías, es el que más difiere de todas las demás. Sus temas son excepcionalmente hermosas y sus armonias tienen momentos de sutileza y audacia. La instrumentación e imaginativa y demuestra un dominio completo de la forma clásica. La interpretación de Diemecke fue respetuoso al sentido de la partitura, sin ser rutinario, con un alto sentido de profesionalidad y exigencia sonora. Su versión cuidó los aspectos técnicos como el equilibrio sonoro, el fraseo y la precisión. La Orquesta Filarmónica respondió de forma entusiasta y correcta. La obra respiró un cierto aire de distinción muy agradable que fué calidamente apreciado por el público.

Alexandre Moutouzkine

Alexandre the Great Captures, Enraptures Audience at the Greenwich Symphony

By Linda Phillips

Flashback: The incredible young pianist Alexandre Moutouzkine first showed Greenwich audiences his astonishing artistry in the Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto #3 in 2012 with the Greenwich Symphony, a performance which left the audience collectively gasping.

Last weekend, in the final concert of the Symphony’s 57th season, the work he played was the massively pyrotechnical Liszt Piano Concerto #2, with lots of runs, flourishes, octaves, arpeggios, trills and very little thematic material. While he astonished with his presence and fantastic technique, we wanted more: a real concerto, with discernible movements. And we didn’t even receive an encore from the gifted young man in a black tailcoat after a standing ovation and many cries of “bravo.”

Conductor David Gilbert announced the works, and gave background information on the pieces to be played and on the inside history of music, introducing many of us to Mottl, a great conductor of the late 19th century who championed Berlioz and Chabrier, and collaborated with Gluck.

Opening with the Gluck-Mottl Ballet Suite #1, the orchestra sounded the work’s major theme, with French horn prominent. Section two was consonant and sweet going from minor key, with major resolutions. In the third section French horn and flute spoke, Light and sprightly, the section contained an excellent motif by flutist Helen Campo. A light, romantic section followed, with the entire work courtly and rather majestic.

Alexandre Moutouzkine took the stage for the Liszt with a command that extended to his greeting of Concertmaster Krystof Wytek, then turned his prodigious talent to the keyboard, where he issued the four sections, encapsulated in one unbroken movement, moods changing and drama surging, with total mastery.

The quiet opening, with clarinet prominent, led to broken chords in piano, the on to astonishing runs, where Mr. Moutouzkine showed his absolutely perfect dynamics.

Dramatic and florid, Adagio sostenuto assai contained runs and a solo by the pianist that was dark, and repeated in the orchestra. It ran immediately into Allegro moderato, quiet, the cello picking up the melody from piano in a duet. Allegro deciso was markedly 4/4, with the piano repeating a sequence of chords. Allegro animato was a breathtaking scampering in the keyboard, dramatically underscored by kettle drums. Moutouzkine was astonishing, riveting.

To call Mr. Moutouzkine’s performance “flawless” would be to belittle it.

Preternatural, perhaps?

Brahms Symphony #1, sometimes called “Beethoven’s 10th, is a beautifully scored work (Brahms was a master of orchestration) and the opening was commanding, capturing with orchestral balance and comprehension the beautiful tumult of Brahms’ mind and emotion. The pounding opening of un Poco Sostenuto was akin to the beating of a pounding heart, the oboe sounding mournfully. Andante Sostenuto, stately, slow, was exalted, with French horns, woodwinds and brasses featuring and a solo by Concertmaster Wytek. Un poco allegretto e grazioso in a sprightly movement, leading to the majestic theme of the fourth movement, which ends with the full passion, vigor and understanding of the composer, and contains the symphony’s recognizable theme. As Brahms said of his compositions, “I take dictation from God.”

This season, the GSO has taken a leap forward in its performance artistry: Scheduling an array of great symphonic works, and playing them with intensity and an organic unity.

And Mary Radcliffe, president of the GSO Board of Directors, presented the GSO’s 2015 Music Award to cellist Emily Azzarito at the Sunday performance. Pianist Alicia Wang also won the award — both students with great promise.

For information on the upcoming 58th season of the GSO, go to www.greenwichsymphony.org

Photo credit: E. Appel

Linda Phillips’ classical music reviews have won four “Best Column of the Year” awards from the Connecticut Press Club, and have been nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in Criticism. She is the author of the novel, “To The Highest Bidder,” nominated for a Pulitzer in fiction.

Alexandre Moutouzkine

Por Emilio Sanmiguel Especial para El Nuevo Siglo LOS APLAUSOS del respetable fueron tan calurosos, que Alexandre Moutouzkine resolvió regalar, no uno, sino tres encores al final de su recital de la noche del pasado sábado en el Teatro de Colsubsidio: Lilacs de Rachmannov, El otro estudio y Nina con violín.

Fue el perfecto final para un concierto marcado por la excelencia. Porque Nina con violín de Ernán, así, sin hache, López-Nussa es una composición cubana, una danza en realidad, que Moutouzkine interpreta con tanta autoridad en el estilo que hasta la ha tocado en el Encuentro de jóvenes pianistas 2014 de La Habana.

Final perfecto para una noche que abrió con su versión limpísima de la Suite francesa no 5 en sol mayor de Johann Sebastian Bach, porque resultó imposible sustraerse a la firma extraordinaria y reflexiva como recorrió su inmortal Sarabande, la gracia absoluta del Bourée, la finura de la Gavotte y el impresionante control de las “voces” de que hizo gala en los movimientos extremos de la suite: la allemande y la gigue final.

Enseguida vino la transcripción de Sergei Rachmaninov sobre tres movimientos de la Partita no 3 en mi mayor para violín solo, también de Bach. Si en la Suite Moutouzkine fue escrupulosamente cuidadoso del estilo, en la transcripción sí se permitió ciertas libertades. Lo interesante de lo que hizo fue que cada uno de los movimientos lo inició con la máxima pureza estilística, sonido controlado y nada de pedal, pero a medida que avanzaba, especialmente en el Preludio y particularmente en la Gigue, el sonido se ampliaba paulatinamente hasta alcanzar dimensiones avasalladoras, pero, esto fue lo más importante, sin que el sonido perdiera calidad, sin descuidar la musicalidad y manteniendo la más absoluta limpieza; los movimientos de la Partita parecían venir desde el siglo XVIII para llegar a la grandilocuencia sonora del romanticismo tardío de principios del XX.

La primera parte cerró con su transcripción de tres escenas del “Pájaro de fuego”, el ballet de Igor Stravinski. Difícil pasar al papel lo que en el teatro fue pianismo de altísimo bordo. Porque hubo pirotecnia virtuosística, sin duda, pero también derroche de musicalidad. Primero por el atinado criterio en la selección de los fragmentos: la brumosa y etérea primera escena del ballet, luego el chispeante Pas seule del pájaro de fuego y finalmente la desbordada Danza infernal, pero es que además la suya no fue una transcripción, digamos, literal, sino selectiva, que tomó partido por los acentos más osados e innovadores de la partitura original, de la cual se dice, le dio sepultura al pasado y sentó las bases para La consagración de la primavera.

La segunda parte estuvo consagrada a los “12 Estudios, op. 25” de Federico Chopin. Otro suceso pianístico, porque las legendarias dificultades del ciclo, parecieron no plantearle ningún tipo de problema técnico, sino que a la hora de la verdad se convirtieron en un inmejorable vehículo para hacer música de la mejor calidad; es decir, que no hubo rastro alguno de virtuosismo en su manera de resolver los estudios y sí pasión, limpieza y gracia.

Un recital, sin duda, excepcional, por eso no fue sorpresa la recepción del público que, como dije, salió ampliamente recompensado y con el sabor cubano de esa Nina con violín del cubano López-Nussa

Hoy puede ser una gran noche

Las noches muy excepcionales no suelen ser las más frecuentes en la magra vida musical de Bogotá. Por eso la Serie internacional de grandes pianistas ocupa el lugar que ocupa en el menú cultural local. La de esta noche tiene todos los visos de una experiencia de esas llamadas a ser recordadas por mucho tiempo.

Porque El Arte de la Fuga BWV 1080 es una de las obras cumbres no del barroco sino de la historia, y jamás ha sido tocada en Colombia, en su versión para teclado. De hecho hay toda una polémica respecto de cuál debe ser el medio más adecuado para llevarla al público, y hasta algún audaz ha resuelto especular que es una partitura para ser oída mentalmente; y todo parece indicar que el teclado es el medio más adecuado para hacerlo.

El pianista franco-suizo Cëdric Pescia la llevó al disco y los comentarios de la crítica especializada no han ahorrado elogios; la ha interpretado ya en muchos escenarios; de hecho acaba de hacerlo en Bruselas. Esta noche es el turno para Bogotá.

Sin exagerar puede decirse que la de esta noche es toda una prueba para el público. Porque en El Arte de la fuga el auditorio se va a enfrentar con una composición colosal en sus objetivos, que deliberadamente evade las exhibiciones de virtuosismo o cosas por el estilo, para darle cabida a la inteligencia del interprete puesta al servicio de una música cerebral, matemática, cuya belleza emana de la profundidad del pensamiento del más grande compositor de la historia.

Interesante la expectativa que despierta cuál vaya a ser la reacción del público, porque la última fuga de la obra quedó inconclusa, la enfermedad no le permitió al compositor terminarla, la música sencillamente se diluye y el público de Bogotá jamás ha vivido una experiencia similar.

Alexandre Moutouzkine

Pianist Alexandre Moutouzkine at Zinc Bar

-Connecting New Yorkers with Cuban Idiom and Russian virtuosity -

THURSDAY, JANUARY 15, 2015

at 7 PM, (doors 6.30 PM)

Tickets $25

BUY TICKET HERE

82 West 3 rd Street

(Btw. Thompson & Sullivan)

New York, N.Y. 10012

“Moutouzkine does not fail to impress with his crystal clear melodic sense of line, sensitive expressiveness, and powerful, pianistic facility.”

-Ilona Oltuski-

In 2009, music journalist Ilona Oltuski founded GetClassical.org to share her enthusiasm for great talent and to further classical music’s presence within today’s nightlife scene. WWFM has engaged in a partnership with GetClassical and will broadcast GetClassical performances to its wide audiences. Contact at Ilona@getclassical.org for further information on events and to read Ilona’s blog, GetClassical.

About the Artists:

In 1995, Moutouzkine left his native Russia for Hannover’s reputable Hochschule für Musik until, according to the artist, “something really important” happened in his life. Solomon Mikowsky, the old school pedagogue at Manhattan School of Music heard him perform, and convinced by his talent and personality, secured him a place as his pupil in 2001. “He was definitely the most transforming influence for me,” says Moutouzkine. He (Mikowsky) was also the one, revealing the ingredients of Cuban, and South American music to me, which had never been part of my vocabulary before. “Music,” he describes, “that holds at the core something ethereal, with incredible traditions and sonorities.” As pedagogue at his Alma Mata, Moutouzkine’s goal is to continue to inspire his students and help them to develop both pianistically, and as performers.

“I always tell my students that this whole way of getting superficial attention via social networks etc. does take a lot of time and energy, which might be better spent where it really counts – with the music.” He is more open- minded about participating in audience-friendly projects, as long as there is substance to build on: He opened Astral Artist’s 2012/13 season with a concert including a commissioned animation, entitled Who stole the Mona Lisa, accompanied live by Moutouzkine, performing his own transcription of Stravinsky’s Firebird.

As a performing artist he is always looking for that “intoxicating level of greatness, connecting with great art and with the meaning behind it…It is that energy, which comes from the music itself, these sounds that embody a message…as a performer you are in the ocean, with the movement of the music, and when the wave rises – and you catch it – it raises you, and your audience.”

Alexandre Moutouzkine

Pianist Alexandre Moutouzkine – modernist Cuban idiom and Russian virtuosity in New York

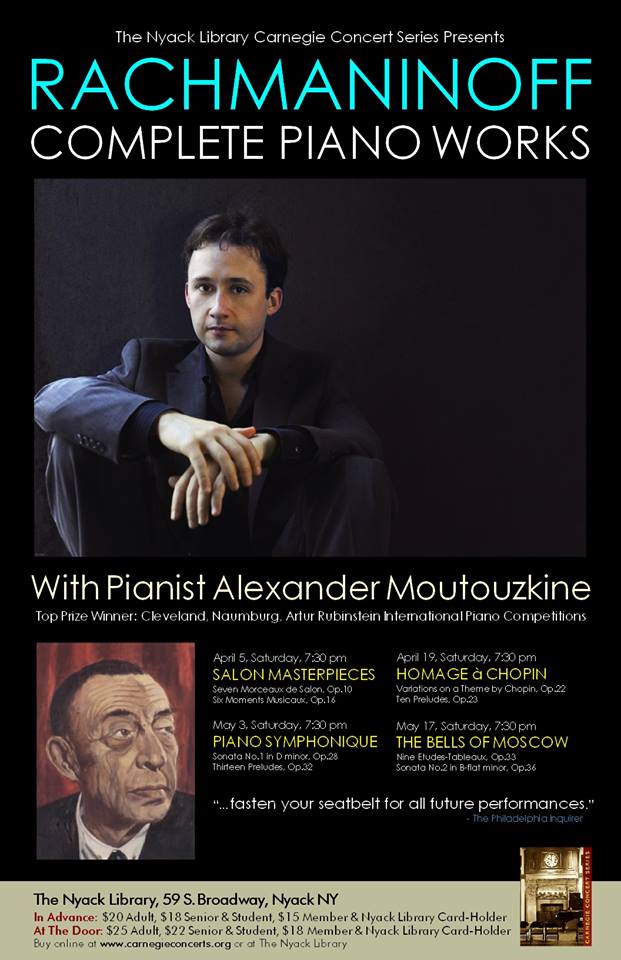

Currently featured in no less than seven all-Rachmaninoff piano recitals at the renowned Carnegie Series at the Nyack library, three of them still to be heard, Russian-American pianist, Alexandre Moutouzkine, does not fail to impress with his crystal clear melodic sense of line, sensitive expressiveness, and powerful pianistic facility.

This week at Merkin Hall, Moutouzkine gave a sampler of his take on Rachmaninoff in the first half of his recital, exploring the romantic resonance of the Russian master’s preludes, awesomely engaging his listeners, filling every corner of the hall. Moutouzkine followed up with contemporary fare, and concluded the mid-day recital with his own transcription of Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite.

The performer’s humorous, yet unpretentious accompanying remarks aided in connecting the performer with his audience, and made it fun to follow the lines of new repertoire. His banter was especially effective in introducing several compositions by living Cuban composers. He shared from the stage: “My revered teacher, Solomon Mikowsky, who, born in Cuba (of Russian-Polish descent) always said to me: ‘to get that special Cuban feel and rhythm – you have to have it in your blood.’ but nevertheless, I hope that through all the lessons, all the screaming…perhaps one drop of that blood of my mentor has entered my bloodstream, or at least my visceral system.”

Alexandre Moutouzkine

Photo Credit: Ellen Appel

The pianist made a convincing case for that drop of blood running in his veins, and for the Cuban pieces by composers Leo Brouwer, Guido Lopez-Gavilan, and Ernan Lopez-Nussa, which held those sensuous rhythmic idioms and jazzy lilt typically associated with the musical language of the region, despite their contemporary, mostly abstract, configurations.

In 1995, Moutouzkine had left his native Russia for Hannover’s reputable Hochschule für Musik (Theater und Medien) until it, according to the artist, “somehow happened” that Mikowsky heard him perform and secured a place for him as his pupil at Manhattan School of Music, in 2001: “It was a new world for me, and it opened doors for me [that] I would not have otherwise known existed,” says Moutouzkine. “I did not have money for a flight to New York, nor for a taxi ride for that matter; he invited me, and it clearly was the step that changed my life. Always, when you get to a new place, everything filters into your playing, new ideas [and] new energy always translate musically, and I grew all along during these formative years. But out of all the influences I received, he most definitely was the most transforming one.”

Of Mikowsky, Moutouzkine says, “he was also always brutally honest. No small talk, no flattery, and no coaxing. But at the end he always came through for me,” the artist describes. “When I had just arrived, minutes before auditioning for the scholarship I so depended on, Mikowsky just took me aside, saying, “don’t worry, you probably won’t get it, but you may as well play…” And he held on, rather stubbornly, to all of his opinions.

“He also was the one who revealed the ingredients of Cuban music to me. South American music had never been part of my vocabulary before, something ethereal, with incredible traditions and sonorities,” he says, and “for introducing me to that world [alone], I have to be eternally thankful. There is this special knowledge of how to treat ‘time’… one of the big secrets in music.”

Photo Credit: Ellen Apple

Sometimes personal accomplishments counted more for Mikowsky than competition laurels, even if it was hard to pinpoint an attitude of praise: “At one point, I was introduced to the legendary Alicia de la Rocha, who I had never heard about before; that certainly put me on a new path and a new program, which brought me to the Zaragoza competition as a young pianist, and then the Van Cliburn in 2001. While I only got a discretionary award, my performance had been broadcasted on the radio, and I received a letter from a woman in federal prison thanking me for my touching performance. Showing him the letter, upon my arrival, he said: ‘Alex, now I am really happy for you, and can see a bright future for you playing in all the jails throughout the United States.’”

Photo Credit: Van Cliburn International Piano Competition

Moutouzkine has certainly inherited his mentor’s somewhat restricted and unforgiving stance on collective success, accomplishment, and praise, seeing it as something standing in the way of the never-ending search for the fulfillment of artistic promises: “As a performer you don’t ever really feel accomplished, it would be counterproductive to the whole process, the continuum of being creative. New York certainly is the right place to be inspired with so much to offer, you just need the energy to fully take advantage,” he says.

Moutouzkine himself is a bit weary of the general direction of self-promotion used these days by young performers who feel pressured to get creative on social media platforms in order to further their reputations, given the lack of performance opportunities for them at established institutions.

In 2013, Moutouzkine joined the faculty of his Alma Mater, the Manhattan School of Music, and says, “I always tell my students that this whole way of getting superficial attention does take a lot of time and energy, which might be better spent where it really counts – with the music. Ok,” he admits, “there should be a good balance. You don’t have to not announce your events on your facebook page…but ultimately, if you concentrate on getting the real work done, other things will fall in place.”

Photo Credit: Yi-Fang Wu

Moutouzkine himself has been taken on by different management during different areas of his emerging performance career, including Astral Artists, whose 2012/13 season he opened with a very original concert that included a specially commissioned animation entitled Who Stole the Mona Lisa, accompanied live by Moutouzkine performing his own transcription of Stravinsky’s Firebird. The performance was repeated in its entirety at Philadelphia’s Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts.

Perhaps this example best illustrates that while self-proclaimed talent on facebook may not count as press or facilitate artists’ recognition, participation in audience-friendly artistic projects may definitely contribute to an artist’s career advancement – if, as Moutouzkine says, “there is substance to build on.”

Moutouzkine’s greatness lies in the elusive product of personality, technical knowhow, and the artistic transparency of his expressivity – and this quality isn’t something you can necessarily achieve through practice. “It is that level of greatness that is intoxicating, connecting with great art and with the meaning behind it all…rarely achieved, but always strived for. It is that energy, which comes from the music itself, these sounds that embody a message…as a performer you are in the ocean, with the movement of the music, and when the wave rises – and you catch it – it raises you – and your audience. It’s magic, and all about that energy that is in the sound, just like ultrasound has the power to heal; music can change everything on a molecular level. But on stage you are in the moment, you can never play the same exact way again, but you have that energy and what you do with it – like in real life – is up to you in that instant.”

In the spirit of shared passion for bringing classical music to alternative venues and in his support of GetClassical’s efforts to reach new audiences, Moutouzkine will perform at GetClassical’s new series at Zinc Bar on January 15th, 2015.

More info on that to come on http://getclassical.org

Alexandre Moutouzkine

Four Play

Chamber Music International opens the season with a terrific foursome's exciting performance of Dvořák.by J. Robin Coffelt

published Sunday, September 21, 2014

Friday night’s concert of chamber works at Dallas City Performance Hall, the first concert of Chamber Music International’s season, featured some of the most delicious, juiciest Dvořák heard in that hall in a while.

Pianist Alexandre Moutouzkine, violinist Carmit Zori, violist Atar Arad and cellist Bion Tsang collaborated for an at turns moving, exciting, and lyrical Piano Quartet in E flat Major in the second half of Friday’s program. All four musicians pointedly emphasized Dvořák’s quirkier harmonies, especially in the first movement, helping listeners to hear aspects of the piece that might have eluded them in previous encounters. In the second movement, Tsang’s lyrical solo passages were as gorgeous and nuanced as they should have been, and the fourth movement was ferociously electrifying. The concert was well worth attending just to hear this piece.

Alexandre Moutouzkine began the program with three of Rachmaninoff’s Op. 23 Preludes: No. 1 in F sharp Minor, No. 11 in G flat Major, and No. 5 in G Minor. The No. 1 is contemplative and subtle; Moutouzkine’s delicate phrasing was exemplary here as well as in the No. 11. The No. 5, with its thundering bass, is much more virtuosic, and its character borders on bombast. Moutouzkine achieved high-Romantic ardor here perfectly, without making it a caricature of itself.

The evening’s performance of Mozart’s Divertimento in E flat Major for Violin, Viola, and Cello was somewhat more mixed. There were many glorious moments throughout the six movements, including Atar Arad’s utterly gorgeous and substantial viola sound. Especially in the first movement Allegro, the members of the trio did not seem to have the same ideas about tempo, and there were some intonation problems. Still, by the final movement, violinist Carmit Zori tackled especially difficult passages with cleanness and precision.

These are four top-level musicians each with a substantively different style and approach. Watching them work together, even when the results were somewhat imperfect, as in the Mozart, was a lesson in how to approach collaborative musicianship. Listening to them play the Dvořák, in contrast, was a lesson in how music should be.

Friday’s concert was dedicated to violinist Ik-Hwan Bae, a frequent collaborator with CMI, who died this year at the age of 57.

Alexandre Moutouzkine

New Amsterdam Symphony Orchestra

Peter Jay Sharp Theatre at Symphony Space

$20; Member, Student, Senior $14; Child $12

MUSIC

More Major minors: Two more giants of the symphonic repertoire - both in C minor: Winner of many top prizes at renowned competitions, Russian-born pianist Alexandre Moutouzkine performs Rachmaninov's beloved Piano Concerto No. 2; conductor Guerguan Tsenov concludes the program with Brahms magnificent Symphony No. 1.

More Major minors: Two more giants of the symphonic repertoire - both in C minor: Winner of many top prizes at renowned competitions, Russian-born pianist Alexandre Moutouzkine performs Rachmaninov's beloved Piano Concerto No. 2; conductor Guerguan Tsenov concludes the program with Brahms magnificent Symphony No. 1.

The Dallas Morning News said Russian-American pianist Alexandre Moutouzkine, "played Brahms' Op. 117 Intermezzi more beautifully, more movingly, than I've ever heard them. At once sad, tender and noble, this was playing of heart-stopping intimacy and elegance."

Highlights of the upcoming season include a return to Philadelphia's Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, chamber music concerts with violinist Mikhail Simonyan at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. and the Bremen Musikfest, debut appearances with the West Virginia Orchestra, Flint Symphony, and the Bay-Atlantic Symphony and performances of "Between the Keys," a program of complete solo piano works of John Corigliano.

Mr. Moutouzkine has toured throughout Germany, France, Spain, Russia, Italy, and North and South America, as well as in China and Japan. In recent seasons, he has appeared as soloist with the Tivoli Symphony Orchestra, the Radio Television Orchestra of Spain, Cleveland Orchestra, Louisiana Philharmonic, Valencia Philharmonic, the Gran Canaria and Tenerife symphonies in the Canary Islands, the National Symphonic Orchestra of Panama, the National Symphonic Orchestra of Cuba, the Israel Philharmonic, and the Brno Philharmonic Orchestra of the Czech Republic. His recital in London's Wigmore Hall was hailed by International Piano magazine as "grandly organic with many personal and pertinent insights offering a thoughtful balance between rhetoric and fantasy…technically dazzling." Mr. Moutouzkine's performance of Chopin Études in the Great Hall of the Moscow conservatory was recorded live and released on the Classical Music Archives label in Russia.

The winner of many renowned competition awards, Mr. Moutouzkine claimed top prizes at the Walter W. Naumburg, Cleveland, Montreal, and Arthur Rubinstein international competitions, among others. He is a winner of Astral Artists' 2009 National Auditions, and The Philadelphia Inquirer said of his Philadelphia recital dubut under Astral's auspices, "Moutouzkine's kind of talent has an impact on his surroundings…[he gives] clarity to his musical choices, but heat to the conviction behind them," and went on to say that his is "a career that will matter." Recent highlights include debuts at the Great Hall of the Berlin Philharmonic in Brahms' Piano Concerto No. 1 with the Berliner Symphoniker, a chamber music concert in Lincoln Center's Kaplan Penthouse with the Jasper String Quartet, an appearance with The Philadelphia Orchestra on its "Beyond the Score" series, performances in Colombia, a recital in Puerto Rico, and recitals throughout Asia, including appearances in the Beijing Concert Hall and Japan's Yokohama Hall. The Greenwich Citizen claimed of his recent debut with the Greenwich Symphony in Rachmaninoff's Concerto No. 3 that Mr. Moutouzkine is "poised to join the pantheon of greats…outperforming even the composer himself." Following the success of a performance of his own solo piano transcription of Stravinsky's Firebird Suite, performed live alongside specially commissioned animation entitled Who Stole the Mona Lisa?, he opened Astral's 2012-2013 season with a repeat performance in Philadelphia's Kimmel Center for Performing Arts, to rave reviews.

Alexandre Moutouzkine holds a Master's degree and post-graduate degree from the Manhattan School of Music where he studied with Solomon Mikowsky. He holds undergraduate degrees from the Hochschule für Musik und Theater in Hannover and Russia's Nizhny Novgorod Music Academy. He is currently a teaching associate at the Manhattan School of Music where he also received a 2012 Distinguished Alumnus Award.

Alexandre Moutouzkine

Pianist Alexandre Moutouzkine: Crisp, bright, clean - and finger-busting

September 27, 2011 By David Patrick Stearns, Inquirer Music CriticThe kind of well-groomed, well-tempered talents that arrive at the Kimmel Center are in some ways the best recommendation for refreshingly less-mediated recitals of the sort given Sunday by pianist Alexandre Moutouzkine eight blocks west at the Trinity Center for Urban Life. This young Russian pianist (just a hair over 30), presented by Astral Artists, programmed too much music (Corigliano, Schumann, Scriabin) and talked (however engagingly) at too much length. Yet he offered much to take home - even if, at the time, one struggled to take it in.

The concert also felt like the beginning of a career that will matter. Whether or not he reaches Lang Lang's global heights, Moutouzkine's kind of talent has an impact on his surroundings. The center was packed to the rafters with age groups at both extremes - thanks to his recitals at schools and senior facilities - plus the Russian community. And while his program was a finger-buster, it wasn't flashy; much of the challenge was sifting through vast thickets of notes to find the music's central and most essential ideas - one reason Scriabin's collection of little monsters known as the Etudes, Op. 8, was Moutouzkine's finest achievement.

One couldn't expect the insights that come with decades of living with this music, but Moutouzkine offered musical traffic management of the highest order. His technique is crisp, his sonority bright and clean, but without the eerie ease of Marc Andre Hamelin, giving clarity to his musical choices, but heat to the conviction behind them.

Scriabin's music itself vacillates between Chopin on steroids and a more mature manner that points to the composer's concise later piano sonatas. Even his best melodic ideas are so elaborately framed that you can miss what the framing is for; Moutouzkine made each etude a glimpse into a larger individual world. No. 11 was a detailed soliloquy, while No. 2 felt like an exploration in pure sound. By the end, the piano was significantly out of tune, and Moutouzkine probably could have used an ice pack. Yet he played two encores.

No doubt he earned most audience points with Schumann's beloved Fantasy in C, which began with an explosion of notes - mainly because this is a pianist who lets you hear them all. The composer's mental instability usually seems a million miles away amid this music's youthful extravagance. But rather than creating a warm blanket of sound with his left hand, Moutouzkine maintained an honest clarity that let you feel the fissures in the piece's emotional foundation. His soft playing wasn't just pretty, it was deep.

John Corigliano made an uncharacteristically unbuttoned appearance in the recently composed, three-movement Winging It. Though Corigliano's typical starting point is structure, this piece is mostly improvisations that he recorded and transcribed. You don't need to know that to hear the difference from his other music. Moutouzkine revealed a fascinating recurrence of archaic cadences, some sounding like traditional hymns, others like Renaissance polyphony. I wonder if the composer saw that coming. I certainly didn't.

Read moreAlexandre Moutouzkine

Dear Vera (Wilson, Astral Artist),

Alex was superb!!!! Thank you for sending him to us! What an amazing technique and what an amazing program. Everyone I talked to was amazed at how much energy he had because each piece he played had so much technical brilliance, which he performed so effortlessly. His lyrical side was also so touching. I have honestly never heard the last movement of the Waldstein played so ethereally and so magically. He cast a spell over us all with that last movement which I will never forget.

Alex's master class was also excellent and very informative to everyone. I liked how he would work very carefully with each student, yet also make points directed towards the entire class. At one time he had us all clapping and trying to do triplet vs. duplet rhythms at the same time! It was fun. I, myself, came away with several excellent pointers that I will reiterate to my students today.

He was also most gracious, warm and pleasant and had a lot of fun with my students and others that he met. We would love to have him play here again in a few years.

Again, thank you so much for giving us a chance to hear and meet this wonderful artist. It's been a pleasure to work with you and we're looking very much forward to meeting Di Wu and hearing her recital and experiencing her master class in April.

Gratefully,Fritz

*Fritz C. Gechter, D.M.A*

Alexandre Moutouzkine

A Musical Mélange at CMI

Alexandre Moutouzkine, Yi-Jia Susanne Hou and others make a night to remember at Chamber Music International.by Gregory Sullivan Isaacs

published Monday, February 27, 2012

Richardson — A 100 years or so ago, concert programs were quite different from the carefully programmed ones we attend today. Back then, there would be a jumble of a couple of movements from a symphony, a piano concerto, someone would sing a few arias, a quintet would play and a pianist would knock out some showpieces. The concert the Chamber Music International presented in Saint Barnabas Presbyterian Church in Richardson on Saturday brought this to mind.

There was Beethoven's B flat Major Piano Trio (Op. 11), followed by Arthur Honegger's Rhapsody for flute, clarinet, violin and piano. Then a violinist played two unaccompanied works: Bach's Preludio from his E Major Partita (BWV 1006) and a rarity, Eugene Ysaye's bizarre Sonata for Jacques Thibaud in A Minor, Op. 27 No. 2. The program ended with César Franck's Piano Quintet. A very 19th century evening, indeed.

What was very 21st century was the consistently high level of the performance and technical mastery from all involved.

Russian pianist Alexandre Moutouzkine has been a local favorite ever since he won the Special Award for Artistic Potential at the 11th Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. All of his considerable musical skills, especially his subtle phrasing, were on display. Flawless technique is expected these days, but Moutouzkine makes perfection look easy. In the Beethoven trio, the Honegger Rhapsody and the Franck Quintet, he was constantly in contact with the players, turning his head frequently to watch first violinist Ik-Hwan Bae. Many fine pianists don't do this in chamber music, mostly because they are so tied to the score. Moutouzkine has the score in front of him for reference only and can thus indulge in the luxury of making eye concert with the players throughout the performance. This is just one of many things that set him apart.

Flutist James Scott and clarinetist John Scott (the program doesn't mention any relation) only played the Honegger but, with the sensitive contributions of violinist Ik-Hwan Bae and Moutouzkine at the piano, it was a standout performance. This is a work that is rarely played but deserves more exposure. It is luscious in its post-Debussy chromatic language and the group played it beautifully.

The excellent violist Susan Dubois joined Bae, Hou, Lewis and Moutouzkine for an ardent reading of the Franck. This is passionate music that needs to be played in the hot fever of the romantic spirit and that they certainly did. Although they never crossed the line into blatant sentimentality, they certainly wrung every bit of ardor and fervent romanticism out of every note.

Alexandre Moutouzkine

EL NUEVO SIGLO BOGOTA – February 17, 2012

THE TELLURIC STRENGTH OF ALEXANDRE MOUTOUZKINEAt first sight, Alexandre Moutouzkine seems harmless, almost a little shy, with the kind of shyness that audiences like.

But don’t be fooled by appearances, because once he sits down at the piano, his attitude changes and so does his physiognomy. And the greatness of this pianist emerges according to the circumstances at hand.

Last Sunday, on the fourth recital dedicated to Beethoven’s 32 sonata cycle, the great artist revealed himself to be up to the task of the last work, the Appassionata: he slightly curved his back, approached the keyboard like a beast before its prey, and performed the first chords of the Allegro assai with supreme delicacy. Then, following the markings of the score, he launched into the fortissimo which determines the dramatic character of the work, flooding the hall with a sonority that was frankly telluric but also absolutely controlled. Of special note was Moutouzkine’s ability to control the changing sonorities of the first movement, a quality that he maintained in the second movement, Andante con moto. Here Beethoven asks the interpreter to double the tempo of each successive variation, an octave higher, a lesson in technique and expression. Of course, he reserved all his artillery for the final movement, Allegro ma non troppo, which was the crowning glory of a concert that the audience justly appreciated and expressed with roaring and thundering applause. Alexandre Moutouzkine had earned this appreciation from the first notes.

He opened his performance at a very high level with the Sonata in C Major Op. 2 No. 1, in which the second movement, Adagio, shone with a solemnity that clearly announces the depth of spirit of the sonatas which follow.

The first part of the program closed with the first of the sonatas in the third style, No. 28 en A Major, Op. 101 which does not portray the vehemence of the Appassionata. Instead, this sonata demands depth and intimacy, a characteristic of the last five sonatas; within the framework of an exceptional interpretation, Moutouzkine reached new heights in the two final movements which joined as one.

The second half of the program opened with the Sonata No. 4 which Beethoven himself named the Grand Sonata, which of the 32 is the most extensive, after Hammerklavier; it was brilliantly performed. Moutouzkine overcame the legendary difficulties of the Molto allegro e con brio, and exhibited the greatness of the masterful Largo con espressione. The third movement, Allegro, was performed with imagination while the final Rondo sounded fresh and at times, somewhat mysterious.

Alexandre Moutouzkine

Philadelphia Inquirer

As soloists, splendid; together, superlativeNovember 08, 2011|By David Patrick Stearns, Inquirer Music Critic

Though Astral Artists is in the business of helping promising young talents be all they can be, one can never be sure what form that might take. And while violinist Kristen Lee probably would have given a substantial recital whatever the circumstances Sunday at the Trinity Center for Urban Life, the breakthrough aspect was her duo partnership with pianist Alexandre Moutouzkine.

No pairing since violinist Soovin Kim and pianist Jeremy Denk has exhibited the kind of synergy with which the two both supported and competed with each other in the best possible way. Often, they seemed bent on topping each other, not with sparkle and brilliance (though such qualities were certainly there) but with specificity of insight and of characterization in a big, varied program of Poulenc, Adams, Ysaye, Messiaen, and Brahms.

Moutouzkine's September recital and Lee's performance of Ysaye's Sonata No. 3 for solo violin proved they're wonderful on their own. But as a team, they both become more individualistic - perhaps because they allow each other that extra degree of freedom?

As a result, one's superficial expectations of any given piece were upended. Though Poulenc's Sonata for Violin and Piano is said to reflect his horror over World War I, one rarely hears that element amid the composer's trademark light touch. But the lyrical slow movement took on unusual intensity of concentration with Lee, while Moutouzkine found pockets of dark coloring elsewhere that put everything around it in a different perspective.

The meditative repose that lies beneath most of what Messiaen wrote came with vital tempos and a strong pulse in his Theme et Variations. Though unlike anything I've ever heard, the performance convinced you this is how it should always be. John Adams' Road Movies, a lighter-weight work full of lots of lyrical gestures that reach upward, seemingly to an endless landscape, had all the necessary vitality but also found that one note in any given passage that makes the difference between music that's extremely engaging and seriously witty.

The second theme group of the Brahms Violin Sonata No. 3 first movement had a liquid quality that transcended the music's bar lines while maintaining strict control over the momentum, and moved from there into a performance in which every passage had an insistent distinction: Ideas built on one another, but each had a strictly separate message.

Lee, who'll be featured in Astral's Dec. 3 Philadelphia Brahms Festival, was on her own with the Ysaye sonata, a piece with so much surface dazzle you could easily assume that's all there is. Not with her. The music felt so substantial as to withstand comparisons with similarly unaccompanied works by Bach.

A word about the encore, which was Debussy's Clair de Lune. Nothing seemed special at the outset, but the performance (as well as the rest of the concert) was dedicated to Astral's recently deceased artistic director, the beloved Julian Rodescu. One can laud him for his achievements, but the Lee/Moutouzkine performance was an ideal tribute; it went well beyond the piece's pictorial qualities and became a lullaby that showed just what depths of emotion music can contain without the outlines becoming distorted. Few people in the community will be missed as much as Rodescu. But consider what he inspired here.

Alexandre Moutouzkine

Stamford Advocate

Shouting ovation for Greenwich SymphonyJeffrey Johnson

Published 9:09 p.m., Monday, April 16, 2012

Ever hear of a shouting ovation? In the classical music world standing ovations are not uncommon. But people shouted when Alexandre Moutouzkine finished the final chords of the Rachmaninoff Third Piano Concerto in his performance with the Greenwich Symphony in Dickerman Hollister Auditorium at Greenwich High School Saturday. Yes, there were scattered "Bravos," but most reacted more viscerally. They shouted and hooted. Then, with noise filling the hall, they stood.

Few pianists can play the Rachmaninoff third piano concerto because of its demands on technique, concentration and endurance. Moutouzkine transcended these demands with intellectual clarity. He was able to articulate connections within the work that few manage to consider simply because they are busy with the notes themselves. A great example of this was the figuration in the development of the first movement as it built toward its climactic centerpiece.

Moutouzkine brought out the complexity of the counterpoint, creating a dialogue of multiple ideas in the music. Pianists choose between two possible cadenzas in the first movement of this piece, and Moutouzkine elected the darker, more dramatic and powerful of the two, often referred to as the "ossia" cadenza. This was a good choice for him because it allowed him to demonstrate his voicing control in the lowest register of the piano.

Moutouzkine also juxtaposed the playfulness of the articulate and playful dialogue between the piano and orchestra in the second movement with passionate lyricism, so the edges between these attitudes became blurred. The sense of this juxtaposition was further developed in the finale, and the explosive technical command during the final pages of the work left us in awe. Then, it was all over but for the shouting.

Moutouzkine offered an encore, playing an amazingly super-charged, virtuosic transcription of the Rachmaninoff "Polka Italienne." The first half of this program was no less extraordinary. "We are in a mood to celebrate," said conductor GSO David Gilbert, "it has been a wonderful season, we had a great time, and this program could not be better for that purpose." The event opened with Rossini's overture to "La Scala di Seta." This piece was easy on the ears and filled with lovely musical humor. But for all its sonic joy, it is a challenging work to perform because its lines are completely exposed, and because nothing goes wrong quicker than things that are supposed to be witty and fun. The Greenwich Symphony made it fun, and the brilliant performance was led by nimble and articulate oboe playing by Randall Wolfgang.

Next we heard the orchestral suite "The River" by Duke Ellington. I was thrilled to hear this played live. Gilbert had a personal connection with the work because it was premiered in 1971 with the American Ballet Theatre, where he was principal conductor from 1971-1975. This work has the classic American charm of steak and whiskey. It was an effective blending of influences and styles from the classical music world, with influences from big band, swing and even an essay into tango. The first half of the program closed with an after-dinner mint; "Alborada del Gracioso" by Ravel.

Gilbert was right; this was a season to celebrate. And the Greenwich Symphony programs for 2012-2013 are even more reason for celebration: they are the most adventurous of any orchestra in Connecticut. Let the celebration begin. Jeffrey Johnson is a professor of music at the University of Bridgeport who has written books on music for Dover Publications and Greenwood Press. He can be reached at jjohnson@bridgeport.edu.

Alexandre Moutouzkine

The Washington Post

Violinist Mikhail Simonyan at the Kennedy Center’s Terrace TheatreBy Robert Battey, Published: April 1

Russian violin virtuoso Mikhail Simonyan offered bracing readings of two big sonatas — Brahms’s D Minor and Prokofiev’s F Minor — framed by shorter works of Arvo Part and Karol Szymanowski at a well-attended recital at the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater on Saturday afternoon.

Simonyan, who first appeared at the Kennedy Center in 2001 (at the 35th anniversary gala) is still in his 20s but projects unruffled, seasoned mastery. His bow-arm is a thing of wonder, powerful and seamless. He displayed a perfect, biting sautille stroke in Ottokar Novacek’s “Perpetuum mobile,” offered as an encore, and his hammering strokes in the second movement of the Prokofiev rang without ever scratching. His left hand is fleet and accurate, although the vibrato lacks variety and the natural beauty of the finest artists.

Certainly the Prokofiev was the high point of the recital, considerably aided by pianist Alexandre Moutouzkine, who found interesting and unusual textures in his music but never overbalanced Simonyan. The two artists captured the epic quality of the piece with deep understanding and a broad frame of aesthetic reference.

In the Brahms, Simonyan’s general carelessness with rhythms, and a willful pushing and pulling of tempos, marred the music from the first phrase onward. This otherwise-superlative artist would do well to re-examine the piece, with particular attention to how his parts are supposed to fit in with the those of the pianos.

The Szymanowski Nocturne and Tarantella is a rarely heard gem, and Simonyan’s flawless technical dispatch enhanced its impact.

The concert was presented by the Washington Performing Arts Society.

Alexandre Moutouzkine

Alexandre the Great and a "Rach" for the ages

Greenwich CitizenThursday, April 19, 2012

Crowned by a performance of Rachmaninoff's Third Piano Concerto, commonly known as the "Rach 3," and regarded as the most difficult ever composed, the 54th season finale of the GSO had it all: Great programming, a wonderful orchestral performance, and Alexandre Moutouzkine.

Remember his name, as you'll be hearing much more of this young pianist, poised to join the pantheon of greats.

With an admixture of music of many eras and styles, the performance also included works by Ravel, Rossini, and Duke Ellington in a deeply satisfying, well-paced concert.

At the Sunday afternoon concert, Mary Radcliffe announced the winner of the annual Dorothy Gluckmann Award, violinist Anastasia Dolak, of New Fairfield.

Conductor David Gilbert commented that the orchestra was going to show off, and remarked on the GSO's history of finding young artists on the verge of important careers. Of Moutouzkine, he commented that he "owned" the "Rach 3," displaying the stamina, technique, and the poetical sense that the work demands.

Opening with Rossini's Overture to "La Scala de Seta," (the Silken Ladder), a musical romp of romantic intrigue, buoyantly scored, with the orchestral opening cascading to portray the ladder being lowered for a lover, the work featured oboe, flute and French horn, moving to a scurrying passage of pizzicato strings, a typical Rossini romp.

"The River," a ballet score by jazz great Ellington and originally composed for The Alvin Ailey Dance Company, is in seven sections (echoing Shakespeare's Seven Stages of Man?) and represents life's journey as a moving stream. Spring opens with a figure in French horn, with bell-like xylophone and the kettle drum signifying birth itself.

"Meander" began in a low bleat of horns in dissonance, with jazz-like chords and the thrill of the harp. A flute broke in, leading to a jazz sequence, with hot rhythm and jazz kicks. Suddenly the music went to tempo, the tuba sounded and the flute wandered into a cadenza.

"Giggling Rapids" was antic, opening with piano, a jazzy dance band whirling like a flight of bumblebees. With percussive kicks, the character was like a Broadway show tune played by a big band. "Vortex" opened sotto voce, with pizzicato basses and flute, castanets clicking, cello and oboe in a luscious close.

"Lake" was jazzy, Ellingtonian, with a 4/4 boogie beat. "Twin Cities," where the trickle finally joined the Mississippi, was somber, throbbing, with cymbals joining. A four-square chorale with a harp plinking behind the stately, portentous theme led to the swelling finale.

Conductor David Gilbert cited the brasses and woodwinds, and the audience erupted into "bravos."

Maurice Ravel's "Alborada del gracioso" from the original piano suite, "Miroirs," is a Spanish, driving, virtuosic orchestral work. The GSO was up to the percussive, Flamenco style, pounding themes, interspersed with romantic melodies, always taken up-tempo.

The orchestra gave an accomplished reading of a work, combining swooningly romantic passages with rhythmic Flamenco parts.

Moutouzkine, greeting Concert Master Krystof Wytek, appeared in a black tailcoat, intriguing, as the heat in the auditorium had caused male orchestral members to doff their jackets.

Beginning Rachmaninoff's "Piano Concerto No. 3 in D Minor, Op. 30," his articulation was perfect in Allegro ma non mato: powerful when needed, exquisitely tender in romantic passages. The soloist gained power in the cadenza, achieving breathtaking arpeggios and holding the sostenuto pedal, interestingly, through some transitions.

Intermezzo adagio, with its poignant orchestration, and the cascading emotion of the piano as it entered, calm and questioning, was sheer poetry.

Moutouzkine performed another heart-wrenchingly beautiful cadenza with soul, heart, and mastery. But the "Rach 3," like the human heart, is always restless, and called for reprises in the brasses and woodwinds.

Finale was taken very up-tempo, staccato, with astonishing crescendos, a slow chorus of brasses and woodwinds and then a ripple in the keyboard. An intense and passionate melody broke out, the flute singing. The thrumming, swelling chords reached crescendo, more pedal attacks by the piano and the orchestra swelled to the finale.

The eruption of bravos was sustained, and after the fourth curtain call the soloist played a jazzy, Gershwinesque encore by fellow Russian Nikolai Kapustin, "Etude 7, Intermezzo."

Had we, the audience, ever really heard the "Rach 3" before? Or been so intensely moved and involved before? The simple answer is "No, we had not." Moutouzkine brought out previously unnoticed secondary melodies in the left hand, and utilized the sostenuto pedal to great effect, outperforming even the composer himself. Elegant, emotional and virtuosic, his was a performance to be treasured by an artist of true genius.

Of the concert, a friend, a life-long music lover, said it was "the best she had ever attended." That sentiment was echoed by the audience, and by this reviewer.

For information on the upcoming 55th season of the GSO, visit www.greenwichsym.org, or call 203-869-2664.

Alexandre Moutouzkine

Outstanding Young Alumni Award

Alexandre Moutouzkine (MM ’01 / PS ’04 / AD ’05), has appeared as piano soloist with such ensembles as The Philadelphia Orchestra, Cleveland Orchestra, Israel Philharmonic, and Brno Philharmonic Orchestra of the Czech Republic. He recently debuted at the Great Hall of the Berlin Philharmonic in Brahms’ Piano Concerto No. 1 with the Berliner Symphoniker. His recital in London’s Wigmore Hall was hailed by International Piano magazine as “grandly organic, with many personal and pertinent insights, offering a thoughtful balance between rhetoric and fantasy…technically dazzling.” The winner of many renowned piano competition awards, Mr. Moutouzkine claimed top prizes at the Walter W. Naumburg, Cleveland, Montreal, and Arthur Rubinstein international competitions, as well as winning the Astral Artists’ 2009 National Auditions.

Classical music review: Chamber Music International delivers skillful surprises

By Scott Cantrell Classical Music Critic scantrell@dallasnews.com

Published: 27 February 2010

Chamber Music International's Saturday-night concert was imaginatively programmed and played with great flair as well as skill. With a typical assemblage of performers from hither and yon, treacherous high violin and cello lines in the Shostakovich Piano Quintet weren't always fastidiously tuned. But these were momentary distractions in a performance deeply felt and wisely gauged. And the first half of the concert, at Southern Methodist University's Caruth Auditorium, was pretty fabulous.

The opening Suite for two violins and piano could pass for Erich Wolfgang Korngold. Oozing turn-of-the-20th-century charm, the four movements marry palm court and concert hall.

In fact, it was the work of Moritz Moszkowski (1854-1925), a German pianist and composer of Polish descent. His compositions are largely forgotten, but early recordings preserve his celebrated (if to our ears eccentric) pianism.

It's hard to imagine a performance with more affection and pizzazz than that served up by violinists Jun Iwasaki and Ik-Hwan Bae and pianist Alexandre Moutouzkine. The piano part could have used a little more projection, but the Caruth Steinway's treble sounded a bit muted all evening.

Iwasaki and Moutouzkine gave a bang-up account of American composer Paul Schoenfield's Four Souvenirs: a "Samba" that really gets down, a dreamy "Tango," a surprisingly gentle "Tin Pan Alley" and, with quite a bit of boogie-woogie mixed in, a virtuoso "Square Dance."

On his own, Moutouzkine made Ravel's La valse high drama, from opening rumbles, to waltzes that really danced and stretched their legs to an orgiastic climax.